A reader asks:

My relationship with my husband of 8 years is struggling. I’ve been trying to improve things, but most of the advice out there seems geared toward people who have a lot of conflict in their relationship. My husband and I rarely fight, but things just seem to have gotten distant and stale. Any insight into why this happens and what we can do to turn things around?

Recently, I was organizing a bunch of old files and came across a note I made to myself from my days doing therapy, and it that said:

Why relationships get stale: 1) Skimming 2) Skirting 3) Squashing

While I hadn’t thought about that note and the ideas in it for years, it all came back to me in a flood, the main idea of which is this:

Relationships get stale because we stop tending to each other’s emotions. This is not unlike flowers in your garden: If you stop tending to them, they’re likely to wither and dry out.

Of course there are many other reasons a relationship can get stale. But this lack of tending to each other’s emotions is a big one that almost no one seems to talk about.

And in my experience, there are three specific habits couples fall into that leads to this: Emotional Skimming, Emotional Skirting, and Emotional Squashing

NOTE: If you prefer to watch or listen, there’s a video version here →

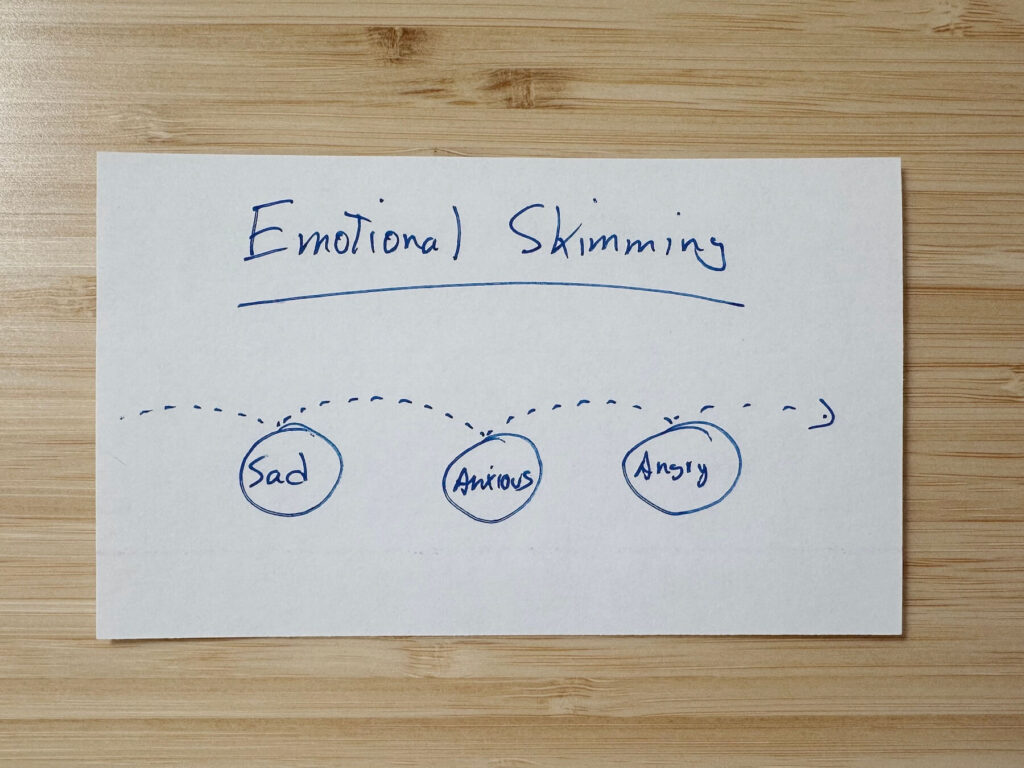

1. Emotional Skimming

Emotional skimming means only briefly and superficially acknowledging your partner’s emotions.

While rarely done intentionally, emotional skimming easily morphs into a habit. And when one or both partners perceive that how they feel is not of interest to or only superficially acknowledged by the other person, distance grows and intimacy shrinks.

Put another way:

People don’t get lonely in relationships for lack of connection; they get lonely because they lose emotional intimacy.

A great way to break this pattern of emotional skimming and rebuilding emotional intimacy is to practice asking open-ended questions, which are questions that invite storytelling, elaboration, and depth rather than simple yes/no answers. For example: Instead of You okay? try Gosh, what was it like for you to hear that?

While conceptually simple, having the presence of mind to actually use open-ended questions in practice is often a challenge. But when you get in the habit of inviting your partner to go deeper, the depth of your emotional intimacy tends to increase as well.

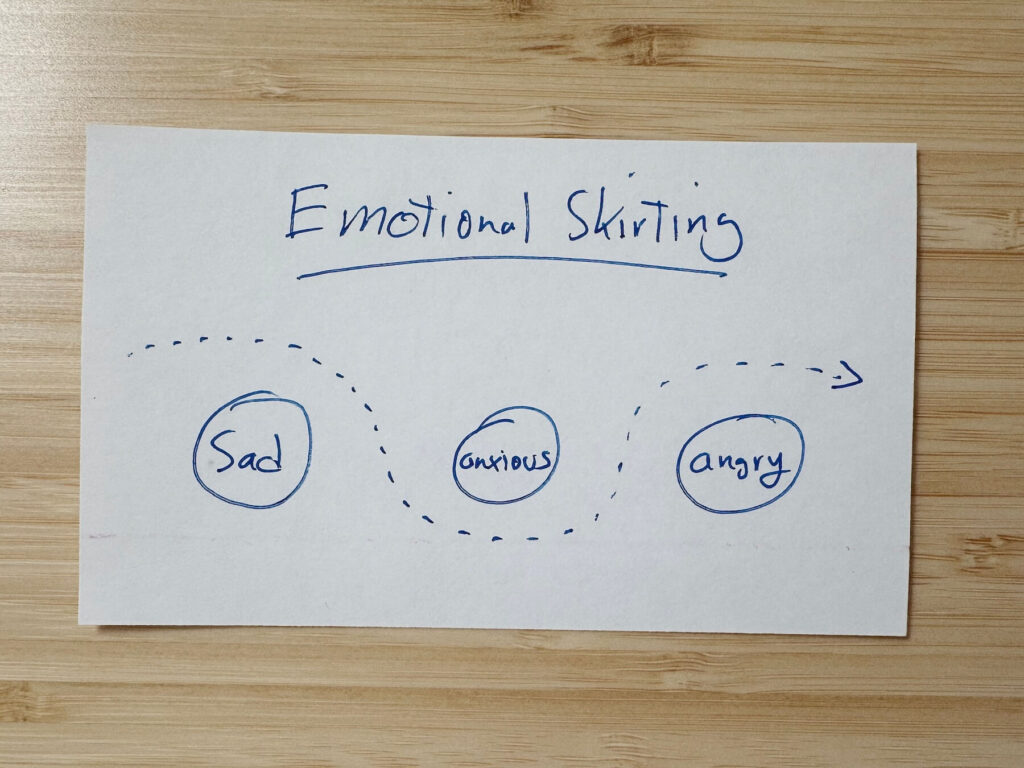

2. Emotional Skirting

Emotional skirting means avoiding certain situations because they might involve difficult emotions that you don’t want to deal with.

For example: If your partner tends to be anxious and stressed after work, you might, only semi-consciously, schedule lots of activities for that time so you don’t have to be home to deal with it. Like emotional skimming, emotional skirting involves avoiding the temporary discomfort of confronting and tolerating an emotion in exchange for the long-term pain of relational loneliness and low intimacy.

A good way to break this cycle is something I use with my clients called The Emotional Check in. If you find yourself in a habit of either skimming or skirting your partner’s emotions in the moment, simply make a point to return to them later. For example: It seems like you were pretty overwhelmed earlier today. Sorry I wasn’t more attentive at the moment. But I wanted to check back in on that and see how you were doing.

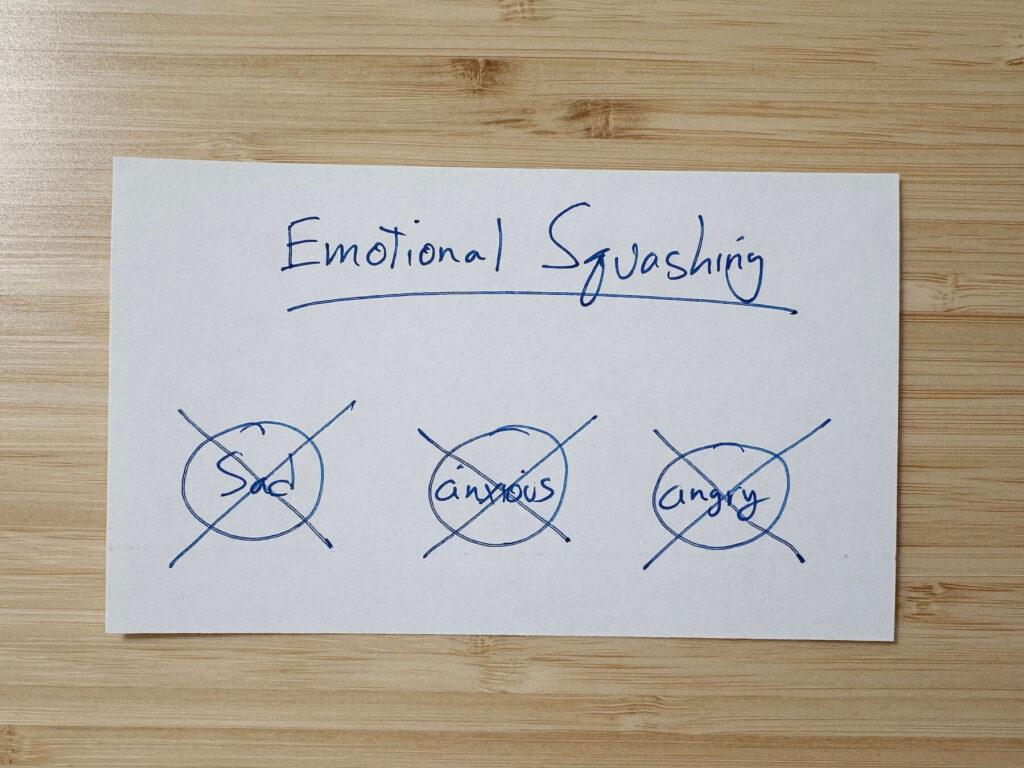

3. Emotional Squashing

Emotional squashing means actively criticizing, invalidating, or otherwise trying to discredit or get rid of your partner’s emotions.

For example:

- It’s ridiculous that you’re getting so anxious over nothing.

- Just stop with the anger already. Calm down and be rational.

- Typical… Anytime I make a new suggestion, you get all hurt and defensive.

Now, most of the time when people engage in emotional squashing, they’re not deliberately trying to be mean or hurtful. They may not even realize that they’re being invalidating or overly-critical. And quite often, it’s a defense mechanism they’ve developed as a way to avoid anxiety.

So, if you see any of this in yourself, relax: Being overly-judgmental with yourself about your tendency to be overly-judgmental with your partner’s emotions is unlikely to help things.

Here’s a little mantra that’s helpful, and one I use to remind myself to be validating of my partner’s emotions (that’s right… I also fall into this tendency to emotionally squash more than I’d like to admit!):

Validate the emotion, criticize the action.

Sometimes we do need to be critical of our partner, give tough advice, or make an assertive request. The trick is to remind ourselves internally—and them out-loud—that it’s okay for them to feel whatever they feel emotionally. You’re criticizing or asking for them to change an action or behavior—which is something they can actually control—not an emotion.

For example:

- It makes sense that you feel anxious after a meeting like that. I’d probably feel the same way. But I don’t think continuing to worry about it is very helpful.

- It’s okay that you feel angry when I make a suggestion you don’t like; but I don’t like it when you respond back to me with sarcasm.

Three Final Thoughts

First, you might be thinking to yourself…

That’s all well and good, but I’m not the problem. It’s my partner who needs to work on this stuff!

While that may be true to some extent, chances are you also have plenty of room for improvement in at least one of these areas. And what’s more, your best shot at encouraging your partner to tend to your emotions better is to model doing the same for them.

Second, this concept of how well (or poorly) we tend to people’s emotions applies to more than just romantic relationships…

- Very often business partnerships go stale because of these same issues of emotional skimming, skirting, or squashing.

- Similarly, important relationships at work with a key team member or manager, for instance, deteriorate because of how emotions are or are not tended to.

- Certainly relationships with other family members—children, parents, siblings—are subject to these same principles.

Third, and maybe most importantly, how you tend to your own emotions impacts the quality of your relationship with yourself, and consequently, other people.

If you struggle with chronic anxiety, self-criticism, imposter syndrome, depression, or any other number of emotional health struggles, it’s very likely that the core problem involves an unhealthy relationship with your own emotions.

So it’s worth asking not only the extent to which you skim, skirt, or squash the emotions of others, but how much do you do it with yourself?

Next Steps

- Watch or listen to the video version. I have a video version of this answer which you can watch here →

- A Helpful Resource. If you’re interested in improving the quality of your relationships by communicating more effectively, I think you’ll enjoy this guide I wrote: 3 Habits of Emotionally Strong Couples →

- Work with Me. Especially if you’re interested in the last point about the importance of building a better relationship with your own emotions, I teach a course called Mood Mastery that’s all about improving emotional resilience by cultivating a healthier relationship with yourself.

- Ask a Question. Got a question you’d like to hear me answer? Anonymously submit a question here → and I’ll try to answer it in a future video.